The story of my life during the years leading up to my retirement could have been recorded in ten-minute installments, patient after patient, day after day. This is in keeping with the trend toward shorter and shorter sound bites, 280 character tweets, and snarky comebacks that have come to replace the leisurely, thoughtful exchange of ideas that human beings have always enjoyed, and/or depended upon.

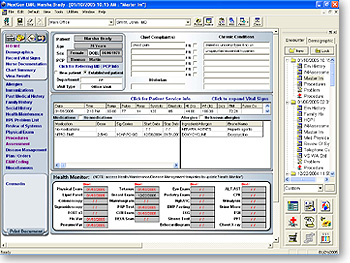

Nowadays, rather than dictating a note about the patient encounter (a.k.a. narrating the patient’s story), you open an electronic medical record. This is intended to expedite the ten-minute appointment. After all, as a physician you have productivity quotients to meet, and income to generate. Whether you recognize your patients or not.

The EMR presents you with a confusing array of bulleted items, complicated charts, and abbreviated details. You can tell what symptoms were problematic at the last visit, when they started, how often they occurred, and how long they lasted. You know what tests you ran and what treatment you ordered, but you might not remember the patient because nothing else about his or her story is recorded there. He looks like any other older patient with diabetes, or heart failure, or COPD…because you missed the fact that he’s a decorated Vietnam veteran. You can’t understand why your pregnant patient is so anxious because you failed to ask about her sister…who had three miscarriages in a row. You don’t know because you didn’t record the whole story. There just isn’t enough time for that in a ten-minute slot, and there is virtually no place to enter it into the EMR.

Unexpected details like these rarely emerge as part of the history taking process. When the patient is seeing you for a straight-forward problem, these details are often missed. They are dismissed as unimportant or extraneous when, in fact, they may hold the key to the diagnosis, and to the patient's response (or his failure to respond) to treatment.